Frostbite (congelatio in medical terminology) is the medical condition where localized damage is caused to skin and other tissues due to extreme cold. Frostbite is most likely to happen in body parts farthest from the heart and those with large exposed areas. The initial stages of frostbite are sometimes called “frost nip”.

Classification

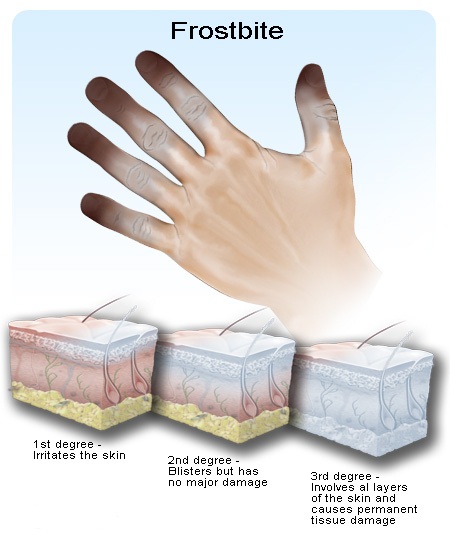

There are several classifications for tissue damage caused by extreme cold including:

- Frostnip is a superficial cooling of tissues without cellular destruction.

- Chilblains are superficial ulcers of the skin that occur when a predisposed individual is repeatedly exposed to cold

- Frostbite involves tissue destruction.

Stages:

At or below 0 °C (32 °F), blood vessels close to the skin start to constrict, and blood is shunted away from the extremities via the action of glomus bodies. The same response may also be a result of exposure to high winds. This constriction helps to preserve core body temperature. In extreme cold, or when the body is exposed to cold for long periods, this protective strategy can reduce blood flow in some areas of the body to dangerously low levels. This lack of blood leads to the eventual freezing and death of skin tissue in the affected areas. There are four degrees of frostbite. Each of these degrees has varying degrees of pain.

- First degree

This is called frostnip and this only affects the surface skin, which is frozen. On the onset, there is itching and pain, and then the skin develops white, red, and yellow patches and becomes numb. The area affected by frostnip usually does not become permanently damaged as only the skin’s top layers are affected. Long-term sensitivity to both heat and cold can sometimes happen after suffering from frostnip.

- Second degree

If freezing continues, the skin may freeze and harden, but the deep tissues are not affected and remain soft and normal. Second-degree injury usually blisters 1–2 days after becoming frozen. The blisters may become hard and blackened, but usually appear worse than they are. Most of the injuries heal in one month, but the area may become permanently insensitive to both heat and cold.

- Third and Fourth degree

If the area freezes further, deep frostbite occurs. The muscles, tendons, blood vessels, and nerves all freeze. The skin is hard, feels waxy, and use of the area is lost temporarily, and in severe cases, permanently. The deep frostbite results in areas of purplish blisters which turn black and which are generally blood-filled. Nerve damage in the area can result in a loss of feeling. This extreme frostbite may result in fingers and toes being amputated if the area becomes infected with gangrene. If the frostbite has gone on untreated, they may fall off. The extent of the damage done to the area by the freezing process of the frostbite may take several months to assess, and this often delays surgery to remove the dead tissue.

Risk factors:

Risk factors for frostbite include using beta-blockers and having conditions such as diabetes and peripheral neuropathy.

Causes:

Factors that contribute to frostbite include extreme cold, inadequate clothing, wet clothes, wind chill, and poor blood circulation. Poor circulation can be caused by tight clothing or boots, cramped positions, fatigue, certain medications, smoking, alcohol use, or diseases that affect the blood vessels, such as diabetes.

Exposure to liquid nitrogen and other cryogenic liquids can cause frostbite as well as prolonged contact with the chemical butane.

Treatment:

Do not make affected area (skin) touch any cold or hot objects. Keep affected area warm. Treatment of frostbite centers on rewarming (and possibly thawing) of the affected tissue. The decision to thaw is based on proximity to a stable, warm environment. If rewarmed tissue ends up refreezing, more damage to tissue will be done. Excessive movement of frostbitten tissue can cause ice crystals that have formed in the tissue to do further damage. Splinting and/or wrapping frostbitten extremities are therefore recommended to prevent such movement. For this reason, rubbing, massaging, shaking, or otherwise applying physical force to frostbitten tissues in an attempt to rewarm them can be harmful. Caution should be taken not to rapidly warm up the affected area until further refreezing is prevented. Warming can be achieved in one of two ways:

Passive rewarming involves using body heat or ambient room temperature to aid the person’s body in rewarming itself. This includes wrapping in blankets or moving to a warmer environment.

Active rewarming is the direct addition of heat to a person, usually in addition to the treatments included in passive rewarming. Active rewarming requires more equipment and therefore may be difficult to perform in the prehospital environment. When performed, active rewarming seeks to warm the injured tissue as quickly as possible without burning them. This is desirable as the faster tissue is thawed, the less tissue damage occurs. Active rewarming is usually achieved by immersing the injured tissue in a water-bath that is held between 40-42°C (104-108F). Warming of peripheral tissues can increase blood flow from these areas back to the bodies’ core. This may produce a decrease in the bodies’ core temperature and increase the risk of cardiac dysrhythmias.

Surgery:

Debridement and/or amputation of necrotic tissue is usually delayed. This has led to the adage “Frozen in January, amputate in July” with exceptions only being made for signs of infections or gas gangrene.

Prognosis

A number of long term sequelae can occur after frost bite. These include: transient or permanent changes in sensation, paresthesia, increased sweating, cancers, and bone destruction/arthritis in the area affected.